- Accaparement des terres

-

Politiques foncières

- Refonder la politique foncière agricole de la France

- Politiques foncières et histoire agraire en Europe

- Les politiques foncières agricoles de la France au XXe siècle

- Le foncier en Afrique de l’Ouest. Fiches pédagogiques.

- Réformes Agraires dans le Monde

- Expérience du Code Rural au Niger

- Politiques foncières et Réforme Agraire. Cahier de Propositions.

- Forêts

- Eau

- Gouvernance des territoires

- FMAT - Forum Mondial sur l’Accès à la Terre 2016

- Autres Conférences et Forums internationaux

- Conférences filmées - Réunions Thématiques AGTER

- Entretiens avec des membres d’AGTER

- Formation - Enseignement

- Formation - Voyages d’étude

- Formation - Modules courts

- Editoriaux - Bulletin d’information d’AGTER

- Préserver l’environnement et les grands équilibres écologiques

- Développer la participation des peuples à la prise de décision aux niveaux national et local

- Respecter les droits humains fondamentaux. Lutter contre les inégalités

- Mettre en place une gouvernance mondiale efficace. Construire la paix

- Assurer l’efficience de la production agricole. En finir avec la faim

- Valoriser et entretenir la diversité culturelle

- Prendre en compte les besoins des générations futures. Gérer les « communs »

Recherche dans les titres, sous-titres, auteurs sur www.agter.org et sur www.agter.asso.fr

Recherche en plein texte sur www.agter.org avec Google

Rechercher dans le moteur Scrutari de la Coredem (multi-sites)

The territory of life of the Karen people provides a grassroots’ alternative to imposed destructive development in Burma / Myanmar

Case example # 1 of Nourishing life - territories of life and food sovereignty. Policy Brief of the ICCA Consortium # 6

Rédigé par : Michel Pimbert, Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend

Date de rédaction :

Organismes : Indigenous Peoples’ & Community Conserved Territories & Areas (ICCA Consortium), Research Centre, Agroecology, Water and Resilience - Coventry University (UK)

Type de document : Article / document de vulgarisation

Documents sources

Pimbert, M.P. and G. Borrini-Feyerabend, 2019. Nourishing life - territories of life and food sovereignty. Policy Brief of the ICCA Consortium # 6. ICCA Consortium, Centre for Agroecology, Water and Resilience of Coventry University.

Résumé

Extracts from a report prepared for this Policy Brief by Caspar Palmano and Paul Sein Twa, 2019, KESAN website and P.K. Feyerabend Foundation website.

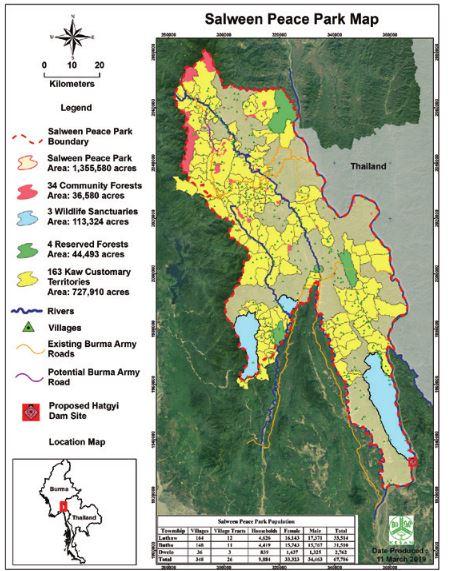

The Salween Peace Park (Kholo Tamutaku Karer) covers 5,485 km2 of the Salween River basin, a region of great importance to global biodiversity in Burma/Myanmar that hosts rare and endangered species— such as tigers, gibbons, pangolins, leopards, elephants and great hornbills. In local history, the arrival of the community in the area is the point at which the Karen calendar begins, 2758 years ago. In the early 1800s, the British colonial government did not significantly limit the Karen’s traditional livelihoods and relations with the territory, but the policies and practices of the Myanmar government after independence have caused the displacement of many communities, and the loss of some community Kaw. In Karen language, kaw means ‘land’… but the term has many layers. A Kaw comprises the ancestral home of a specific Karen community, its lands, forests, rivers, natural resources, flora, fauna, and people. Some kaw are small, with only one village located within, some kaw are large, and host more than ten villages. The kaw embodies the way the community governs and manages the land and natural resources, its culture and social interactions and the health of the community, deeply connected to the health of the lands, waters, and forests in which it lives. A kaw is a self-perpetuating territory, a bio-cultural unit of life.

If, in the sense just described, the Salween River basin has been the kaw or ‘territory of life’ of its indigenous Karen custodians for about three thousand years, the self-declaration of the Salween Peace Park is truly recent (December 2018). The approximately 60,000 residents went through a long and laborious process of successive consultations, developed their own agreed rules and finally proclaimed that their territory was dedicated to fulfilling their own three core aspirations: 1. peace and self-determination; 2. environmental integrity; and 3. cultural survival. In an area that has suffered from over 60 years of civil war, the territory is now dedicated to generating peace and protecting a stronghold of biodiversity and Karen culture (including customary land governance and management systems) from old and new threats.

Indigenous Karen traditions are intimately tied to the land and nature in general. The local food system1 is based on upland Ku rotational agriculture supplemented by lowland cultivation of orchard, agroforestry, fishing, hunting, and gathering of non-timber forest products. Ku is the name that the Karen use for their upland rotational plots — selected and allotted to households within a kaw based on customary practice and cultivated for a limited time (typically between 7 and 10 years), before they are let to regrow naturally. Food and other products are bartered or traded for cash, both internally and externally. Both upland Ku cultivation and lowland agriculture are heavily based on traditional knowledge and know-how, and Karen’s use of land, flora and fauna is guided by local taboos and seasonality. Various communities have established their fish and wildlife conservation zones, community forests and herbal medicinal forests, all regulated by traditional practices. As known to scholars and demonstrated by the Karen in their territory, shifting cultivation does coexist with exceptional biodiversity and may be positive for it.

The Salween Peace Park is a living grassroots alternative to the destructive development (mega hydropower, roads, mining, logging) and poaching and trafficking of wildlife proposed, or allowed by, the Myanmar Government and its allied foreign companies. On the one hand, the territory is the basis of food security for all Karen communities. On the other, the forests and mountains have protected communities from the Burmese soldiers, giving them somewhere to flee to, while their customary knowledge and practices have allowed them to survive even while in hiding. The main constraints to security of food and livelihoods, as well as to the lives of people, are the Myanmar Government’s laws and policies, which do not recognise the rights of the Karen communities to govern their territory and criminalise the traditional shifting cultivation techniques they practice at the heart of their way of life. In fact, you find misery and child malnutrition in Karen communities primarily in the unfortunate circumstances when communities are forcibly displaced, land is confiscated, or crops are destroyed by the Myanmar army.

For the custodian communities of the Salween Peace Park, a major measure of wellbeing and food sovereignty is access to good land, good forest, and good streams to practice agriculture, as everyone depends heavily on that for their food and for livelihoods in general. Other indicators of wellbeing are the level of cooperation within and among communities, the abundance of yield (rice, orchard products) at harvest time, and the happiness of the children. All residents have a similar relationship with the territory, as their culture, practices, and beliefs are deeply intertwined with the landscape and natural resources. Some of them, such as traditional leaders and elders, hold stronger knowledge about nature, but they all equally depend on the territory, and feel responsible to care for it.

1 A ‘food system’ gathers all the elements (environment, people, inputs, processes, infrastructures, institutions, etc.) and activities that relate to the production, processing, distribution, preparation and consumption of food, and the outputs of these activities, including socio-economic and environmental outcomes (HLPE 2014).

The full Policy Brief of the ICCA Consortium # 6 can be downloaded below.

Document Content

-

1/ Territories of life

-

2/ Food Sovereignty

-

3/ Do territories of life advance and secure food sovereignty? Eight case examples:

-

Karen people - Burma / Myanmar

-

Wampis nation - Peru

-

Abolhassani tribes - Iran

-

Djola people - Casamance, Senegal

-

Cañamomo Lomaprieto - Colombia

-

Krayan Highlands - North Kalimantan, Indonesia

-

Shellfishers on foot - Galicia, Spain

-

Xcalot Akal - Mayan territory of Yucatan, Mexico

-

-

4/ Discussion

-

5/ Expanding territories of life & food sovereignty - options for action and practical recommendations

-

6/ Recommendations

Download here The full Policy Brief of the ICCA Consortium # 6

Ressource

Défis

- Les habitants gèrent leurs territoires

- Réduire les émissions de gaz a effet de serre

- Préserver la biodiversité naturelle et domestique

- Reconnaître les savoir-faire des paysans, des pasteurs, des chasseurs cueilleurs, des pêcheurs

- Souveraineté alimentaire

Zone géographique

Voir aussi

- Les voyages d’étude, un outil pour favoriser l’apprentissage et contribuer au changement. (Ed. # 49)

- Viajes de estudio: una metodología para generar procesos de aprendizaje y transformación. (Ed. # 49)

- Study tour; a tool for learning and creating change. (Ed. # 49)

Organismes

Agter participe à la Coredem

Agter participe à la Coredem