- Land grabbing

-

Land Policies

- For a new agricultural land policy in France

- Land Policies and Agrarian History in Europe

- The agricultural land policies of France in the 20th century

- Land issues in West Africa. Briefing notes.

- Agrarian Reforms in the World

- Lessons Learned from Niger’s Rural Code

- Land Policies and Agrarian Reform. Proposal Paper.

- Forest

- Water

- Local Land Management

- WFAL - World Forum on Access to Land 2016

- Other International Conferences and Forums

- AGTER’s Thematic Meetings - Videos

- Interviews with some members of AGTER

- Training - Education

- Education - Study trips

- Education - Training modules

- Editorials - Newsletter AGTER

- Protect the environment and ecological balances

- Develop participation in national and local decision making

- Respect basic human rights. Fight against inequality

- Establish effective global governance. Build peace

- Ensure efficiency of agricultural production and end hunger

- Develop and maintain cultural diversity

- Consider the needs of future generations. Good management of the commons

Title, subtitle, authors. Research in www.agter.org and in www.agter.asso.fr

Full text search with Google

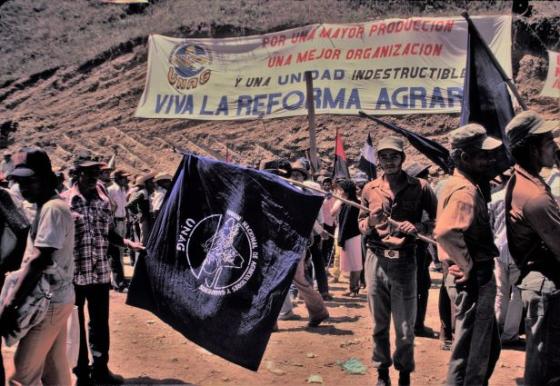

Agrarian reforms are still necessary, but they cannot be identical to those of the past

Written by: Michel Merlet

Writing date:

Organizations: Association pour contribuer à l’Amélioration de la Gouvernance de la Terre, de l’Eau et des Ressources naturelles (AGTER)

Type of document: Scientific article

Documents of reference

Translation and adaptation of the article published as part of report on: “Agricultural land: both a common good and source of tension”. Produced by GREP & Terre de Liens for the journal POUR. Merlet, Michel. Des réformes agraires sont toujours nécessaires, mais sous des formes nouvelles. Revue POUR (GREP) # 220, Dic.2013

Translator : Niels Zwarteveen

Summary

All societies that have experienced endogenous development have been built on relatively egalitarian agrarian foundations. Neither the large estates nor manorial systems of the past catered to the general interest, and today, large agricultural enterprises with wage earners are not compatible with the interests of the majority either. The potentially disastrous consequences of increasing land access inequality and the acceleration of the current changes in agrarian structures around the world will unfortunately force us to resort once again to exceptional policies that many thought were things of the past: « agrarian reforms ». However, if the need to resort to these policies becomes necessary, they cannot be identical to those of the past.

An earlier version of this article was published in French in December 2013 in the journal POUR (GREP) # 220, also available in AGTER’s collection of documentary resources 1.

This analysis is based on the author’s experience of agrarian reform in Nicaragua in the 1980s and his subsequent practice as a land policy consultant in many countries on several continents.

A forgotten policy once again relevant

The earliest known historical references to agrarian reform date back to Ancient Greece. Until the 1980s, many actors, regardless of their ideological leanings, considered that « agrarian reform » was needed only when agrarian structures hindered a country’s economic development. With the generalisation of neoliberal policies and « structural adjustments »2, this policy disappeared from international agendas3 and only a few peasant organisations continued to fight for agrarian reforms.

The failures and digressions of the many agrarian reforms that took place in the 20th century has meant that the decisive role that some of them have played in establishing favourable conditions for development has been overlooked. This was the case in Japan, Korea and Taiwan, but also in China, Vietnam and several Latin American and European countries.

Some World Bank experts contributed to the confusion by proposing a « new » conception of this policy, the « market-assisted agrarian reform », supposedly in response to the shortcomings of previous experiences. With the support of international financial institutions and in the framework of the « fight against poverty », it was promoted in some Latin American, Asian and Southern African countries, replacing the agrarian reforms previously carried out by states. These states then repudiated coercive policies, and land transfers were made only between consenting parties. This policy however failed in every place it was introduced, as only a policy that offered the poor a chance to buy land from the rich, in order to lift themselves out of poverty, ever could!

It was not until 2004 that civil society organisations brought the issue back to the forefront by organising the World Forum on Agrarian Reform (WFAR) in Valencia. This contributed to the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) convening an International Conference on Agrarian Reform and Rural Development (ICARRD)4 in 2006.

Since then, farmers’ organisations have been structured and consolidated at the international level, and forums for consultation and debate between civil society, states and international organisations have been created5. At the same time, however, the concentration of land and natural resources has continued to increase. This situation forces us to re-examine the policy tool known as agrarian reform and the conditions that are required for states to be able to use it successfully again.

What is an « agrarian reform »?

During the 19th and 20th centuries, several agrarian reforms took place in very different political and economic contexts: during the development of capitalism in the countryside both in independent and post-colonial situations, the transition to socialism or, on the contrary, de-collectivisation following the dismantling of the Soviet Union. They were part of very different, even diametrically opposed, political projects and had different objectives too:

-

To correct a situation considered socially unjust such as an unequal distribution of land, for ethical reasons, but also for pragmatic reasons in order to avoid increasing insecurity and violence, for example.

-

To respond to the political interests of a group seeking to consolidate its social base vis-à-vis other sectors of the country (for elections or in the economy) or vis-à-vis foreign forces (strengthening or defence of sovereignty).

-

To make the best use of natural resources, both ecologically and economically, allowing farmers to benefit fully from the fruits of their labour, previously monopolised by landowners, and thus to invest in improving their technologies.

The term « agrarian reform » is used in different ways, with different meanings, and is therefore often a source of confusion. In this article, we will call « agrarian reform » an ad hoc state intervention aimed at correcting a very unequal distribution of agricultural land. Although an agrarian reform may have many components involving different and complementary policies, its basic action always concerns land, with:

-

The expropriation, in whole or in part, of large tracts of land owned by a few lords or large landowners, with or without compensation.

-

The redistribution of this land, either free of charge or through sale or lease, to producers who had no access to it or who had access to it under very unfavourable conditions (very high payments to the owner, either in kind, in labour or in money).

Having established this definition, it is clear that some of the policies presented as ‘agrarian reforms’ are not of the same nature at all. The following two examples apply to many countries.

-

In countries with large tracts of virgin land, state promotion of peasant settlement on the « agricultural frontier » can be an attractive policy for national development and for reducing inequality to land access. But it is not land redistribution and therefore not agrarian reform. Building infrastructure to facilitate the settlement of peasants and distributing land titles on « national » land is politically easier than expropriating and redistributing the land of large landowners. Thus, in the 1960s, when the US pressured Latin American governments to carry out structural reforms to counter the spread of Cuban-inspired revolutionary ideas, many preferred this option, falsely describing it as an ‘agrarian reform’.

-

Agrarian reforms in socialist countries have been characterised by the expropriation of large estates and their transformation into state production units and/or the redistribution of part of the land to the peasants. The transformation of capitalist production units into state production units does not constitute an agrarian reform: it is the transformation of private property into state property, without real structural agrarian change. On the other hand, the redistribution of plots of land to peasants with little land is indeed an agrarian reform. But in many cases, the beneficiaries were forced to collectivise a few years after receiving the land. Sometimes a hybrid form of collectivisation was promoted, in which the redistribution of land was conditional on the adoption of collective forms of production whose framework of operation was defined by the state. These « cooperatives » and associative enterprises often had a short-lived existence, dividing up their land and selling off their assets when state protection disappeared.

-

Some reforms are erroneously labelled as Socialist « agrarian reforms », even when land redistribution is very limited and in fact agrarian counter-reforms are organised, leading to the large-scale disappearance and weakening of peasant structures. Logically, these policies opened the door to large-scale land grabbing by a few capitalists when the socialist regimes collapsed.

An exceptional measure for exceptional times

An effective agrarian reform always implies a radical, vigorous and rapid rethinking of the existing land property relations. The violence that landowners used against landless peasants before, is in some ways reversed against them by the decisions made by those who have taken power. In many countries, landowners are often well represented in legislative assemblies, and for this reason it tends to be difficult for the dominant social classes of a country to vote in favour of a policy that would directly affect at least some of them, even during a deep economic and social crisis. Exceptions have been the agrarian reform of 1950 in Italy and that of Frei and Allende in Chile between 1965 and 1973, carried out within the framework of a normally functioning parliamentary democracy.

By their very nature, agrarian reform policies can be neither ordinary nor permanent: they require particular conditions and a favourable balance of power. That is why they have most often been implemented during revolutions, after an armed conflict that has left the victor with ample room for political manoeuvring, or have been imposed from the outside. They have always been carried out by strong governments, often led by the military.

Such measures have the advantage of rapidly transforming the agrarian structure. But they also carry risks. If the new agrarian and social structures are not quickly consolidated, if their social legitimacy is not sufficient, and if the balance of power between the main actors is not significantly altered in favour of the peasants, it is difficult to avoid a backlash and a reversal.

Some agrarian reforms, such as the one in Mexico in the early 20th century, were the result of major peasant revolts. Others were carried out without major social movements. But in almost all cases, the implementation of these policies has been imposed by states from the top down: logically, the peasants who receive land are seen as being primarily « beneficiaries ». Producer organisations in the reformed sector, when they exist, are often separate from farmers’ organisations in the unreformed sector. This makes alliances difficult. To prevent their re-concentration, reformed land is excluded from land markets: it is forbidden to sell or rent it without state permission. Thus, the « beneficiaries » remain under the protection of the state. They do not have the opportunity to build and learn new forms of land governance that they themselves could control over time.

When the balance of power changes and new power relations are established later on, the principle of a special status for reformed lands is often questioned. The abrupt return to the market usually results in a rapid loss of land for a large part of the « beneficiaries ». Transformations in agrarian structures, however radical they may have been, can be wiped out in a few years, and often, it takes a long time before the conditions for a new agrarian reform are favourable again.

History shows us that land markets cannot guarantee an optimal allocation of land resources. This is not due, as World Bank experts claim, to the imperfect functioning of markets, but to the fact that land has never been and never can be a commodity like any other. Land will always be considered, at least in part, a common good. It may therefore be necessary at some point, to apply an exceptional measure, when the unequal nature of land tenure has become unsustainable and when no other option is able to deliver rapid results. It should be noted that it will always be preferable not to have to do so, if different land governance, effective regulatory mechanisms and appropriate agricultural policies have prevented excessive polarisation of agrarian structures.

Agrarian reform is first and foremost a corrective measure, which cannot be a substitute for land policies regulating access to land in the long run. However, it can contribute to preparing the conditions for a necessary change in land governance. If in most cases, past agrarian reforms have failed to achieve this, it is most likely because they imposed policies on peasants from above, rather than giving them a central role in land transformations. It is also because they did not have a long-term approach to agrarian transformation that gave a central place to the peasantry. This makes it easier to understand why their results have often been short-lived and unsustainable.

What kind of agrarian reforms do we need today?

The recent changes in agrarian structures around the world, analysed in the article on land grabbing in POUR 2013/4 N° 2206, and the global crisis in which they are taking place, are putting agrarian reform back on the agenda. Olivier de Schutter, UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, explicitly called for it in his 2010 report on the Right to Food for the UN General Assembly.

But socio-economic, demographic and environmental conditions have changed a great deal, and today’s agrarian reforms cannot be the same as those of the past. It is no longer a question of fighting against the extensive post-colonial landowners, who appropriated land mainly to control labour, or against the great feudal lords who lived by collecting land rents from their sharecroppers and tenants.

In recent decades, the development of large capitalist agricultural enterprises employing wage labour seems to have finally proven right all those who have long claimed their superiority over small-scale production. It is a system that monopolises land by buying it, but also by obtaining it in concessions or by renting it cheaply and with long term leases from a multitude of small landowners. The growing number of cases of « reverse tenancy »7, especially prevalent in Eastern Europe , in which a powerful company leases a large amount of land, shows that it is no longer necessary to be a formal landowner to be able to appropriate land rent when one has capital and a favourable power relationship. Thanks to their extensive access to financial markets, large agribusinesses use sophisticated technologies, employ few workers per hectare and produce directly for the markets in a globalised trade network. For all these reasons, it gives the impression of being an extremely efficient system, a key element of development and the solution to fighting against poverty. But it is not. The main tools for accumulation in this new sector of large-scale agriculture are not linked to the efficiency of the production process itself, but to three principal mechanisms:

-

The capture of various rents, and in particular ground rent, often through the privatisation of collective communal land, or other mechanisms such as reverse tenancy;

-

A distribution of the value added between workers, landowners and owners of capital that largely benefits the latter;

-

The concentration of value added in certain links of value chains, to the detriment of others, through prices.

In the end, large firms produce less value added per unit area than smaller structures, as many field studies have shown. Their logic is based on a permanent increase in the productivity of their employees’ labour, which allows them to increase their profits. At the same time, they contribute directly to the growth of unemployment and underemployment.

The problem of land grabbing is therefore not limited to the injustice of dispossessing people of their land and the unequal distribution of access to it: the problem is also of an economic and social nature, since it is a question of achieving the most efficient use of land, which is a limited productive resource, and which is why it does not only concern farmers 8.

Some agrarian reforms of the past, such as the Mexican agrarian reform, put communal management of territories at the centre of their system. The ejido system in a way reproduced the traditional function of the indigenous rural community. These peasant communities have existed all over the world, in various forms. Land policies and subsequent changes in Mexico, like agrarian reforms in many other countries, have ignored this intermediate level of governance, and recognised the rights of only the state and the individual. This has had many negative consequences, among which has been the increasing difficulty for a society as a whole to participate in the creation of land policies and their implementation. Since the demographic weight of peasants is decreasing in countries with highly polarised agrarian structures, future agrarian reforms cannot come solely from the pressure of landless peasants. They must respond to the needs of society as a whole, maximise food production and create as many jobs as possible.

Some key theoretical questions for moving forward

An Agrarian reform is always a part of a contradictory dynamic that develops over time. What is important is not so much the immediate result, but the reversal of trends. In order to move forward, the balance of power must shift in such a way that it is always easier to develop actions towards better land distribution, and more difficult to challenge the achievements of this reform.

Different types of land rights exist: rights to use different resources, rights to manage the area, i.e. to establish what can and cannot be done on a given plot, and rights to transfer the rights of the two previous categories. In practice, all these rights are never in the hands of a single holder (the landowner), although the legal frameworks of some countries sometimes indicate this. The different rights may be collective or individual, and are distributed in different « bundles of rights » among individuals, families, social or ethnic groups, different institutions, countries, etc. Very often, the forms of organisation that would allow part of the population to exercise collective rights do not exist (or no longer exist), and the exclusive conception of property does not allow the simultaneous exercise of individual and collective rights over the same parcel of land. Between the state and the people, there is an infinite variety of possible forms of intermediary organisation and ways of jointly managing goods/things that cannot be reduced to a single category of private market goods.

Access to land at any given time is the result of various mechanisms for transferring land use rights and land management rights: inheritance between generations and distribution among heirs, purchases/sales, leases, plunder and conquest, and prescription of prior rights, to list but the principal mechanisms. The market is only one mechanism, among others, for transferring rights. Recognising that there are different kinds of rights and different kinds of rights holders, individual and collective, at different scales, allows for a different and novel approach to the regulation of transfers, whether market or non-market. The challenge then is to create institutions that can manage regulatory mechanisms and that are able to evolve with technology, society and the economy. Latin America’s agrarian reforms of the 20th century mostly failed to do this9. In the end, paradoxically, they allowed for a considerable expansion of land markets.

Land policies are not alone in influencing the transfer of land rights. Fiscal policies on land tenure, transactions and inheritance, economic and monetary policies, rural and territorial development policies, such as encouraging the establishment of young farmers or compensating for regional disadvantages, can have a strong influence on the evolution of agrarian structures. In some cases, the fight against land access inequalities should shift to fighting inequalities created by agricultural subsidies, as has been the case with the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) in the European Union.

In conclusion: an outline of the basic principles for future agrarian reforms

-

They must break with the belief that large-scale production is more efficient than peasant production, which has dominated both liberal and Marxist economic thought. Today, only small-scale, agroecological farming can bring out the best in each territory and preserve the environmental, climatic and social balances that are vital for humanity.

-

They must prioritise the net production of wealth and food per unit area and enable the employment of as many people as possible or allow them a direct productive activity.

-

They have to review their approach to land rights and land distribution.

-

On the one hand, the slogan « land for those who work it » needs to be revisited. It is no longer a question of giving an absolute right of ownership to each producer, but of giving priority to farmers and livestock breeders to gain a secure right for land use, while recognising management rights over the territory for all inhabitants.

-

On the other hand, large capitalist farms with wage earners that do not serve the general interest must also be included among the structures to be divided and redistributed, even if they do not own the land. The new agrarian reforms will therefore also have to affect the rights of use, where these are very unequally distributed.

-

-

They should help facilitate the creation of permanent bodies to regulate land transfers at different levels: the family, the territory, the country, regional areas and, if possible, the planet, to help prevent further land concentration and accelerate the transformation of unreformed sectors10.

-

They can only be promoted if very diverse layers of the population join forces in confronting the powerful national and transnational corporate interests that directly benefit from current land grabs. Like the reforms of the last century, they are likely to require alliances that go beyond national borders, as the threats posed by current developments and the mechanisms that underpin them are global. Promoting agrarian reforms in the 21st century will undoubtedly require more than voluntary mechanisms and codes of good conduct, given the opposition to them from powerful vested interests.

1 www.agter.org/bdf/fr/corpus_chemin/fiche-chemin-376.html

2 Misnamed because it had nothing to do with structures.

3 Land tenure reforms implemented since 1990 in some Eastern European countries have had many similarities with agrarian reforms, but have been presented as land policies related to de-collectivisation, without the term being used.

4 The last FAO conference of this nature had been held in 1979, 27 years ago!

5 The CFS (Committee on World Food Security of the United Nations) has been considered by many to be one of the most thorough.

6 An English version was published in www.agter.org. See Merlet, Michel (2020). Land Grabbing and land concentration around the world: a threat to us all. www.agter.org/bdf/en/corpus_chemin/fiche-chemin-884.html

7 When a large company leases a vast area of land from thousands of smallholders who cannot cultivate it because they do not have the means to do so. This is a common situation in Ukraine or Romania, for example.

8 Over the last 15 years, the experience of the French association Terre de Liens (www.terredeliens.org/) confirms that the inhabitants of a territory are not indifferent to the way in which the places they live in are managed, and that this is not only expressed through their vote in the various elections. By contributing financially to the installation of producers who meet their expectations in terms of the environmental and social choices, the members of this network of local associations claim a share in the management of the land, even if they themselves are not producers. However, the legal framework in force in France obliges them to acquire the ownership collectively in order to exercise this right. The purchase is made with resources provided by numerous partners who benefit from tax advantages. Their actions have made it possible to advance the debate and to show that another policy is possible. But the purchase of land cannot in itself constitute a generalised solution for changing the evolutionary trends of agrarian structures in France.

9 Where land had been redistributed to collective bodies, as was the case in Mexico with ejidos regulating family and individual use, land market expansion was slowed for a long time. However, these collective bodies had difficulty evolving and adapting to change, and fell victim to state political clientelism.

10 Markets are incapable of redistributing land use to the most efficient producers, as neoliberal economics assumes. This is not because they are imperfect, but because land always has dimensions of both common good (at different scales) and individual good.

Bibliography

References of the initial article published by the journal POUR in 2013, with the English versions of the documents, when they exist.

-

Hans Binswanger, Klaus Deininger, Gershon Feder (1993). Power, Distorsions, Revolt and Reforms in Agricultural Land Relations. Policy Research Working Papers. World Bank.

-

Jacques Chonchol (1995). Systèmes agraires en Amérique Latine. Des agricultures préhispaniques à la modernisation conservatrice. IHEAL (Institut des Hautes Études de l’Amérique Latine). Paris.

-

Marcel Mazoyer, Laurence Roudart (1997). Histoire des agricultures du monde. Du néolithique à la crise contemporaine. Éditions du Seuil. Paris

-

Olivier Delahaye (2006). Reforma agraria y desarrollo rural sostenible en Venezuela: algunos interrogantes. p. 93-109. In Fernando Eguren (Editor). Reforma agraria y desarrollo rural en la región andina. CEPES. Lima.

-

M. Merlet, S. Thirion, V. Garces (2006). States and Civil Society: access to land, rural development and capacity building for new forms of governance. Issue Paper No. 2. International Conference on Agrarian Reform and Rural Development (ICARRD) (Porto Alegre, Brasil). www.agter.org/bdf/en/corpus_chemin/fiche-chemin-215.html

-

Michel Merlet (2007). Proposal Paper. Land Policies and Agrarian Reforms. AGTER. www.agter.org/bdf/_docs/merlet_2007_11_land-policies-proposal-paper_en-pt.pdf

-

Saturnino Borras Jr (2007). Pro-poor land reform. University of Ottawa.

-

Laurence Amblard, Jean-Philippe Colin (2008). Reverse Tenancy in Romania: Actors’ rationales and equity outcomes. Land Use Policy 26, 3.

-

Michel Merlet (2012). Rights to Land and Natural Resources. “Land Tenure and Development” Technical Committee. AFD, MAEE, Paris, 2010. www.agter.org/bdf/en/corpus_chemin/fiche-chemin-95.html

Agter is part of the Coredem

Agter is part of the Coredem