- Land grabbing

-

Land Policies

- For a new agricultural land policy in France

- Land Policies and Agrarian History in Europe

- The agricultural land policies of France in the 20th century

- Land issues in West Africa. Briefing notes.

- Agrarian Reforms in the World

- Lessons Learned from Niger’s Rural Code

- Land Policies and Agrarian Reform. Proposal Paper.

- Forest

- Water

- Local Land Management

- WFAL - World Forum on Access to Land 2016

- Other International Conferences and Forums

- AGTER’s Thematic Meetings - Videos

- Interviews with some members of AGTER

- Training - Education

- Education - Study trips

- Education - Training modules

- Editorials - Newsletter AGTER

- Protect the environment and ecological balances

- Develop participation in national and local decision making

- Respect basic human rights. Fight against inequality

- Establish effective global governance. Build peace

- Ensure efficiency of agricultural production and end hunger

- Develop and maintain cultural diversity

- Consider the needs of future generations. Good management of the commons

Title, subtitle, authors. Research in www.agter.org and in www.agter.asso.fr

Full text search with Google

Land Policies and Agrarian Reform. Proposal Paper. Part I. How might the rights of land users be secured? (1 of 2)

Origins and grounds of rights. The different systems of recording and validating rights

Written by: Michel Merlet, (English version: Mary Rodeghier)

Writing date:

Organizations: Association pour contribuer à l’Amélioration de la Gouvernance de la Terre, de l’Eau et des Ressources naturelles (AGTER), Institut de Recherche et d’Applications des Méthodes de Développement (IRAM), Réseau Agriculture Paysanne et Modernisation (APM), Fondation Charles Léopold Mayer pour le Progrès de l’Homme (FPH)

Type of document: Research Paper

Documents of reference

Merlet, Michel. Proposal Paper. Land Policies and Agrarian Reforms. AGTER. November 2007. (English version: Rodeghier, Mary). 120 p.

From the outset, we shall avoid limiting our reflection to “owners”, by attempting to take into account all the beneficiaries and users. This will allow us to highlight the points in common between different situations and treat “ownership”14 as one case among others.

1. Origins and grounds of rights

The first problem that we must address is that of the origin of the rights of individuals and social groups to land. This problem in turn raises that of the recognition of actors, taking into account the different perceptions that each may have of the others and the legitimacy of different forms of organisation and action15. It is impossible to recognise the rights of groups if their identities and essential natures are ignored: therefore it is not only a legal problem, but a social one too.

Despite the risk of simplification, we distinguish two major families of grounds for land rights16:

-

Rights acquired through time, often by the social validation within a power struggle. On the legal level, the mechanism of adverse possession17, (usucapion in Latin) is used in this case: under certain conditions, previous rights cease to be valid at the end of a period whose span can vary considerably depending on the country. These rights are often, though not always, in relation with the labour invested, as an extension of the right to the fruit of such labour.

-

Rights granted by the government (title deeds, sales, donations, etc.). This case is typical of colonial situations, where the legal system seeks to institute this sort of right independently from the first case, even though the government’s power to grant such rights comes under its colonial domination that was acquired through force. The basic instruments in this case are therefore the title deed, which serves as the grounds for the right, and the cadastre (land register)18.

This description would not be complete without mentioning the ideological justifications that can be presented as grounds for rights: thus the invocation of divine rights can take on a variety of forms. According to the solitary doctrine that is now spreading all over the planet, the universal nature of private property and ownership is asserted in a way that recalls the avowal of divine rights.

2. The different systems of recording and validating rights

Recording property rights and information related to them

Different systems for recording property rights, with and without cadastres or land registries, exist around the world. These systems are quite dissimilar and their differences are rooted in history (cf. box 3 and box 4).

In France, the land tenure system does not establish rights in an absolute way. Rather, it is based on a very strong presumption concerning the existence of such rights. In Germany, rights are validated beforehand by judges and are recorded in the land register. In both cases, these rights were constituted progressively through history, balances of power, trials of strength and laws, though they do not stem in the main from the handing over of title deeds by the government.

Box # 3 Two examples of information systems on tenure rights19

The French system of information on land tenure rights20

This is based on the cadastre and on the mortgage registry office. These two institutions operate under the aegis of the Ministry of Finance (Tax Division). It has three basic missions: fiscal (evaluation of real estate and calculating tax bases), legal (identification of estates, owners and their rights) and technical (coordination and verification by large scale maps).

The cadastre was first used during the Napoleonic era for purely fiscal reasons. It simply recorded apparent owners who are liable to pay taxes. Although cadastral documents (maps and plot owners’ records) do not have any official and legal force as such, their progressive involvement in the public announcement of land rights (extracts from the cadastre and plot numbers for spatial identification) has caused jurisprudence to concede that they have some probative value.

The French way to provide public notice of land holdings is done through the registration of deeds granting real (immovable property) rights and their transcription into public records within the local institutions responsible for recording mortgages. According to French law, the basis of a right is the succession of publicly recognised and acknowledged contracts between parties. The contracts are drawn up by notaries (deeds of sales and purchase, and other deeds related to real (immovable property) rights), and filed in the mortgage register.

The German system

The German land registry (Land Book) has a legal role above all else because it is where rights are validated, registered, and made available as public knowledge. The Ministry of Justice is in charge of it.

The Land Book is managed by land magistrates, who examine the substance and form of the rights before registering them. These rights cover all the existing rights within a territory, which are transcribed after having been validated in the registry21. For this reason, reference to the land registry has absolute probative force. The act of registration generates both the deed and the proof of the existence of rights before the parties concerned and third parties.

Estates are subject to obligatory demarcation of boundaries upon the initiative of public decision-making bodies. The land registry is complemented by the cadastre, which describes and identifies the properties. The same ministry or another may be in charge of the cadastre, and it also may be used for tax purposes.

This system certainly provides great security, but it is long and expensive to set into motion.

On the contrary, the Torrens system and the registration systems stemming from it were established in colonial contexts. They still differ from the land registration systems used in the colonising country: the land awarded by the colonial power (and the subsequent issuing of title deeds) constitutes the only acknowledged grounds for rights.

In Latin America, the land tenure regime established by the Spanish and the Portuguese is based on the same reasoning22, which was also that of the colonies of the Roman Empire, as emphasised by J. Comby. The same difficulties are encountered today when recognising the existence of rights that predate colonial occupation in Latin America, Africa, Asia (for example in the Philippines23) and in Oceania.

Box # 4 The TORRENS system and its variants (from J. Comby[>(24) 24] and J. Gastaldi[>(25) 25])

Colonel Robert Torrens developed his system for Australia, at that time part of the British Empire (adoption of the Torrens Act in 1858). It was particularly easy to eliminate any prior occupation right because the Australian Aborigines were not recognised as Australian citizens until 1967. The Supreme Court of this country did not recognise them as being the “first inhabitants” of Australia until December 1993!

In a general way, common colonial practice was as such: after having discovered “virgin” land, the colonial power distributed land plots among the new arrivals. This is what happened in North America after the land was “cleared” of the Indians. Cartographic demarcations were the work of the cadastral survey, the colonial authorities awarded a unit of land to each arrival, and registration in the land registry was equivalent to possession of a title deed. Subsequent transfers of property rights were recorded in the registry. The Torrens system clarified these practices in most colonies.

Although registration is not obligatory, the Torrens system only guarantees rights to registered land. Superficially, it seems to be similar to the German land registry, since once registration has taken place, it is definitive and enjoys absolute probative force. There is no separation between the cadastre and the land registry, and any person requiring registration is bound to carry out a demarcation of boundaries and have surveyors draw up a map. However, this similarity is not deep-set, since the system only recognises the validity of rights granted by the government.

Other registration systems derived from the Torrens system and similar modalities exist. Some of them attempt to take into account certain customary rights, though all of them ultimately follow colonial logic.

The Torrens system perpetuates and institutionalises colonial despoilment. Nevertheless, this is the system that has been used most often as the model for international institutions in their land regularisation programmes. Thus it is easy to understand why such programmes tend to exacerbate conflicts rather than limit them.

Confronted by the evidence (particularly that of the African context), the World Bank had to recognise that private property was not always the best solution for achieving land tenure security. Although it recommended abandoning common tenure systems, dividing common land and distributing plots to private individuals (freehold titles) in 1975, Binswanger and Deininger reported in 1999 that the Bank henceforth recognised that certain forms of common tenure could increase land security and reduce transaction costs26. It also recognised that customary tenure arrangements were changing, that they were not necessarily archaic and that it was advisable to deal with each case individually in order to decide which form of tenure, private ownership or common property, would be the most appropriate27.

Recording multiple land rights and looking for security of land rights. A few African examples

It is impossible to describe the different land rights in use in Africa on the basis of concepts stemming from Western law28. Very frequently, there are more or less exclusive rights of use that belong to distinct social groups and individuals, and which may vary during the year. In southern Mozambique, for example, land is considered to belong to the village or tribal community. Cashew trees belong to certain individuals whereas others have the right to till a field, and a distinct social group may have the right to hunt. These different rights can be transferred in diverse and relatively independent ways.

Etienne Le Roy’s theory of land tenure29, which continues from research done by others30, sets out the different possible ways of regulating man’s relations with land by combining different types of rights (access, extraction, management, exclusion, alienation) and different types of management of these rights (specific to a person, public, common to one or more groups as a function of procedures that can change). André Marty takes a similar perspective when defining priority but non-exclusive rights to water and grazing resources of a tribe of nomadic herders on their home grazing territory. Usually located near a water source, the home grazing territory is developed and maintained by the tribe. It is also a place where they stay regularly at certain times of the year, and which they consider as being their « country ». However, other nomadic groups can also have access to the resources within a tribe’s home grazing territory when passing through, just as a tribe can have reciprocal and temporary access to the homelands of other groups. (cf. record on the specific characteristics of pastoral communities in the Sahel in part 2 of this paper)

Innovative attempts have been made to comprehend such realities made up of bundles of rights. The Rural Land Plans in Ivory Coast, Benin, Guinea and Burkina Faso are illustrations. However, these approaches are complex and difficult. The example of the Rural Land Plan in Ivory Coast is exemplary. (cf. box 5 and box 6)

Box # 5 The Rural Land Plan in Ivory Coast. Interest and limitations (1/2){>(31) 31]

The implementation of the Rural Land Plan in Ivory Coast started with a pilot project (1989-96). The pragmatic and prudent method used is novel insofar as it is a bottom up method, contrary to usual normative approaches. The Plan aims to record existing rural land rights, by fixing boundaries on a map scaled to 1/10,000th and by filing a description in a register for each plot. All the rights as perceived by villagers, the administration and customary authorities are recorded, from use rights to ownership rights, with the agreement and active participation of the parties involved, and without modifying, simplifying or standardising the content. The surveyors record land disputes and simply designate the areas in dispute on the map. They do not attempt to solve any disputes.

The field surveys of property rights are public and contradictory, with minutes being written and signed by the farmer concerned as well as by his neighbours. The results of the surveys are made available during public village meetings, followed by an announcement period lasting three months, during which the results of the surveys are open to objection or correction. The definitive documents are drawn up only after the period of announcement. Their application and maintenance must be effectuated by village committees that are created for this purpose.

In practice, a certain number of technical and linguistic problems arose. For example, the terms for local rights and rules are often difficult to translate into French. Further problems came about because of the administrative procedures inherent to statutory concession; the land requests that could be made on the basis of the land surveys and the certificates issued to the bearers of rights. Recording was done on a plot basis instead of a whole “farm” basis. This made it difficult to take into account the full spectrum of arrangements related to land (delegated rights, rights of non-natives possibly transferable by inheritance, sometimes combined with temporary access in the form of sharecropping to native beneficiaries, temporary transfers, security use, tenancy, etc.).

Nonetheless, the project’s philosophy, which questioned the State’ ownership of unclaimed lands, generated much opposition. As a result, the rights that had been recognised officially were considered above other rights during the registration process. Another substantial concession was that the Ministry of Agriculture was in charge of keeping and implementing the land tenure maps.

The Ivory Coast Rural Land Plan not only showed that it was technically possible to take into account bundles of rights in the constitution of what could be called a « customary cadastre », but also demonstrated that the real problem was in local governance and the social capacity to manage land and resources. We shall return to this subject further on.

Box # 6 The Rural Land Plan in Ivory Coast. Interest and limitations (2/2)

Even though the administration expressed some reservations, individual users were issued receipts and then extracts of the survey once the Pilot Plan was implemented. However, no comprehensive document confirming land rights was issued to the villages. The failure to set up a local authority responsible for permanently updating the land files was another considerable problem because without one, the system was nearly impossible to manage. Furthermore, the lack of such a local authority signed away any possibility to improve local governance over land management.

Although the project showed that it was technically possible to inventory plots and their associated rights at a relatively low cost (estimated at $6-15 US per ha or 25-58¢ per 100 acres) if the plan is implemented nationally), it also showed that this type of operation can be a hollow affair without clear political backing.

The Rural Land Law voted in 1998 (Loi sur le domaine foncier rural) was a victory for the supporters of centralised government land management and privatisation of land resources according to Western conceptions of ownership. It entailed a generalised land registration system. Registration must be demanded no later than three years after the handing over of land right certificates. Land access was limited to the State, local authorities and persons of Ivory Coast nationality, leaving unsecured use rights only to non-naturalised residents of foreign origin, who have not yet obtained the Ivory Coast nationality3233.

Using distinct methods, the Niger’s Rural Code as well as the GELOSE project with the Relative Land Security program in Madagascar also attempted to allow for secure and multiple rights (bundles of rights) over the same land.

Begun in the 1990s, the approach developed for the Rural Code in Niger required much discussion between different social groups. Land Commissions apply this policy through a gradual process entailing the recording, making public, and updating of the different rights of users at the local level. The commissions are made up of customary authorities who play an important role in land management, as well as members of various administrative departments and the representatives of different users. Since they operate on a larger geographic base, the commissions involve a collaboration of neighbouring chiefdoms. The process is far from being complete: the recognition of nomadic herdsmen’s rights is not yet definitive, even though new concepts were included in the Rural Code’s legal texts. Positive progress has been observed in some areas, showing that this method can be efficient, especially when supported by persons not directly involved in the stakes at hand locally34. In a certain way, having started with an approach based on French legal tradition, this process in Niger is moving towards mechanisms that are closer to those of British common law (see box 7).

Box # 7 Two opposing approaches to the recognition of rights in the former French and British colonial empires in Africa35

British colonial administration in West Africa made significant use of local power structures to mete out justice, maintain order and raise taxes. With the exception of a few plantation and urban areas, most of the land was governed by indirect administration and customary law, via local courts and according to principles based on the British tradition of common law. Founded on jurisprudence, common law procedures are very flexible and permit new interpretations in the face of changing circumstances. It therefore upholds close relations with the values of the social group concerned. However, it is also liable to result in violations profiting powerful local interests, and can therefore run counter to the principles of fairness.

The legal system is very different from a coded system that defines from a central position all the rules that must be applied uniformly throughout a country.

The common law and coded law systems result from the last three or four centuries of experience in France and Britain, and cannot be understood without reference to discords originating in the 17th century English Civil War and the French Revolution of 1789.

The types of relationship between the government and the citizens, products of these countries’ revolutionary histories, continue to be expressed within their own legal systems as well as within the administrative and legal systems introduced in the countries they colonised.36

In Madagascar, the Relative Land Security program deserves a closer examination for several reasons37. Christophe Maldidier’s analysis reveals that this program is merely an intermediate step prior to the issuance of genuine property titles.

While steps forward have been taken in Madagascar, Ivory Coast and Niger, the ideological framework, of which absolute ownership is an integral part, endures. A more radical break from this ideology would be necessary. Consequently, systems for recording different types of rights are still far from taking into full account the complex realities of multiple rights found in many African and indigenous societies. Nevertheless, the implementation of diverse new approaches indicates that numerous obstacles have been overcome. There is clearly a real interest in this kind of system, which empowers rural societies to manage their land and natural resources.

Therefore, it is vital to continue these practices while being aware that the process is long, and requires the acquisition of a genuine social capital38 adapted to the present context. The enduring security of rights for the different uses of land and natural resources can be guaranteed only through lasting efforts to establish local democratic institutions capable of ensuring the sustainable management of these rights in the interest of the majority39. (See below).

How to secure the rights of users who are not « owners »: tenants, sharecroppers and beneficiaries of different derived rights?

In developing as well as developed countries, considerable areas of farmland across the planet are worked through systems operated by non-owners. For this reason, providing land tenure security for farmers who are not owners is a highly important matter that concerns millions of people40.

Tenant farming in its different forms (free and temporary allocation, hire, sharecropping, with infinite altercations) is practised in different situations as a function of prevailing land systems. Such practices allow for both the elasticity of tenure and adjustments that would be impossible via sales of land ownership rights41.

Continental Europe provides different and interesting examples of how the tenure of farmers and share-croppers might be secured. Denmark was at the forefront in this area when, in 1786, it adopted a modern tenant farming statute42. Legislation protecting farmers exists in most European countries, where family commercial farm production predominates. Recourse to tenancy generally tends to occur between the members of the same family, and does not play the same role or have the same implications depending on how they are affected by inheritance rules and other laws (there are two main situations which result from the legal system in place: 1) equitable inheritance between brothers and sisters, implying shared property rights among each generation, and 2) the possibility that the farm is not divided through inheritances, i.e. a sort of eldest’s birthright system.

Although the historical inception of the concept of absolute ownership was in France, it is nonetheless in France where the most radical examples of tenure security for tenants and sharecroppers can be found. Adopted in the middle of the 20th century, these policies made it possible to modernise family farming in regions where tenant farming and sharecropping were common practice (see box 9).

Box # 9 The status of tenant farming in France43

The laws on the status of tenant farming date from the forties (amendments of 04/09/43 and 17/10/45 to the French Civil Code, with the inclusion of sharecropping in 1946). At this time, French farming needed to modernise its production techniques. The texts concerning the status of tenant farmers are now incorporated in the Rural Code.

Guaranteed lasting land access for the farmer:

The contracts are written. The minimum legal leasehold is for nine years. Long term leases of 18 to 25 years as well as career leases (whose term is set until the retirement age of the tenant farmer) are also possible.

The tenant is entitled to renew the lease for nine years, except in the case of cancellation for serious reasons or repossession [the lessor can repossess the rented farmland only if it is to be worked by himself or his wife or by a descendant of age or an unconstrained minor, who must both partake in agricultural work (effectively and permanently) and live in the dwellings on the repossessed property].

If the tenant should die, the lease continues for his/her spouse, descendants and ascendants, who partake in farm work or have effectively partaken during the five years prior to the decease.

A tenant that has improved the rented property (through work or investment) is entitled to compensation from the lessor upon expiry of the lease.

The tenant must be given priority in purchasing the land if the owner wishes to sell it, on the condition that the tenant has worked as a farmer for at least three years and has farmed himself the property on sale, as well as on certain conditions related to the « control of farm structures », (pre-emptive rights).

Land rent controlled by the government

The minima and maxima between which the rent can vary are set by the prefecture per agricultural region, for both the land and the farm buildings.

A specific procedure for settling disputes

A specific jurisdiction has been created to deal efficiently with disputes between owners and tenants to ensure that the law is executed effectively. Rural lease courts give primary hearings to disputes involving tenant farming and share cropping statuses. These courts are composed of two owner-lessors, two tenant farmers and a presiding judge.

Working in conjunction with other development policies

The lease contract is subject to “structures control”, a policy that aims to avoid an over-concentration of land and to maintain viable farms. The contract’s validity is bound by these regulations and by the tenant’s need to obtain a farming permit.

The French system affords considerable tenure security to farmers due to the existence of powerful farmers’ organisations and a favourable balance of power at the national level. This policy has not led to a reduction in the amount of land leased out and the original goal to modernise farming has been reached. Landowners have been deprived of much of their rights without the need for an agrarian reform. Furthermore, land rentals for farmland have been cut to a symbolic minimum and farmers have obtained the guarantees necessary to make long-term investments44.

On the contrary, the application of this policy in Spain has led landowners to refuse to rent their land to tenant farmers. The relative weakness of Spanish farmers’ organisations in comparison with French ones is probably one of the main reasons for this policy’s failure in Spain.

Obviously, the scope of this discussion is not limited to Europe. Reflection on the nature of conceded or derived rights and the ways in which they can be secured is also on the West African agenda. The importance of bundles of rights in African land ownership systems raises a number of insoluble problems when use rights are to be secured solely by the granting of ownership title deeds. For a few years now, promising work has been accomplished as far as establishing more secure contracts for delegating use rights between different actors45.

Tenancy is least common in Latin America, whereas the development of rental markets on this continent would be an effective means for poverty reduction by increasing secured land access . This can be explained by this continent’s particular agrarian history, by the impact of the agrarian reform and by the fact that land was procured mainly through the colonisation of virgin territory. In such a context, landowners fear that if they were to lease their land to tenant farmers over long periods of time, they would lose their land rights to their tenants. Their strategy is therefore to keep their tenants in a precarious state through short leases of one year or even as short as a crop cycle, in spite of the disadvantages this represents for the development of economically sustainable and efficient forms of farm production. Such situations, which often go against the greater good, can continue for decades because family farming is more or less ignored by government strategies and farmers’ movements remain unaware of how similar problems are dealt with in other parts of the world.

In fact, several countries around the world have passed legislation aiming to regulate the situations faced by tenant farmers and sharecroppers. For example, there is the legal prohibition of sharecropping in Mali and Cape Verde, as well as in Honduras in a completely different context. Not only were these laws generally not implemented, but also they often backfired when they were applied, frequently resulting in worsened working conditions for poor farmers. Far from condemning any new attempt to give tenant farmers greater tenure security in similar circumstances, these failures once again emphasise that laws merely reflect the political climate at a given time. Significant changes cannot be made simply by passing legislation. Rather, the mobilisation of active and involved farmers and the creation of farmers’ interest groups are essential.

Women’s rights to land

Assuring land use rights turns out to be even more difficult when it involves groups whose rights are not fully acknowledged in general.

Such is the case of women in many regions of the world, in different ways and at different levels. The example given in box 10 provides an illustration.

Box # 10 Women’s rights to land in Central America and the Caribbean: Honduras, Nicaragua and the Dominican Republic

The recognition of women’s land rights is limited by legal, institutional and cultural obstacles that are difficult to overcome even after radical political changes.

In these three countries, the prevailing cultural conceptions of rural societies assign women to domestic chores and reproduction while men do the farming. The direct participation of women in farm production, though considerable, is not given the recognition that it deserves. Although their constitutions declare that all people are equal regardless of their sex, certain agrarian laws and certain underpinnings of civil law discriminate against women.

In Honduras until 1992, the agrarian reform laws recognised solely the male head of household as eligible for land allocations, and thus women were excluded. This was still the case in the Dominican Republic in 1998, with even severer restrictions. In Nicaragua, although the agrarian reform of 1981 recognised a woman’s right to be awarded land directly, by 1990 only 10% of those who received land were female.

Women’s rights to land are often limited by legislation related to the family and couple. The lack of full legal recognition of the union between spouses (Dominican Republic) and the fact that the man is legally defined as the head of household directly effect the recognition of women’s rights to land, as well as their rights in other areas such as access to loans. Lastly, inheritance legislation and customs are so that the sons tend to inherit the land while the daughters inherit other kinds of goods (e.g. cattle).

Improved recognition of women’s land rights demands radical social and cultural changes; modifying the laws is insufficient. The changes underway in certain countries nonetheless demonstrate that things can evolve rapidly, when different policies are applied. This is the case of the land ownership legislation process in some Central American countries. For example, in Nicaragua from 1997 to 2000, 40% of those who had obtained a title deed from the rural land registration office were women, either alone or as explicitly recognised joint owners.

14 Absolute ownership is a myth as far as land is concerned. One should speak of distinct kinds of property rights. The first draft of the universal declaration of human rights used the plural; “properties” are a right. It was changed later for the singular “property” with a completely different meaning. For a historic analysis of the genesis of this fiction during the French revolution refer to J. Comby, “L’impossible propriété absolue”, in the collective work of ADEF, Un droit inviolable et sacré, la propriété, Paris, 1989.

15 Cf. André Marty, “Un impératif: la réinvention du lien social au sortir de la turbulence. Expérience du Nord Mali, approches théoriques et problèmes pratiques”, IRAM, 1997. unpublished, 33 pp.

16 On this subject, refer to Joseph Comby, “La Gestation de la propriété” in Lavigne Delville, Quelles politiques foncières pour l’Afrique rurale? Paris : Karthala, Coopération française, 1998. This only concerns a right’s original grounds, since a right can then be transferred by different types of transactions (purchase, gift, succession, etc.).

17 Adverse possession (usucapion): it is a rule by which long-term, peaceful occupancy of a plot for a certain amount of time grants ownership rights to the occupant. Two kinds of mechanisms are frequent, an ordinary one, which requires occupancy in good faith and documentation to prove it, and the extraordinary one, which does not need to fulfil those conditions, but however requires a longer period of occupancy.

18 A cadastre, coming from the Greek word for list, katastikon, is defined by the International Federation of Surveyors (FIG) as follows: “A cadastre is normally a parcel [plot] based and up-to-date land information system containing a record of interests in land (i.e. rights, restrictions and responsibilities). It usually includes a geometric description of land parcels linked to other records describing the nature of the interests, and ownership or control of those interests, and often the value of the parcel and its improvements. It may be established for fiscal purposes (e.g. valuation and equitable taxation), legal purposes (conveyancing), to assist in the management of land and land use (e.g. for planning and other administrative purpose), and enables sustainable development and environmental protection.” FIG, 1991, cited in (editor C. Parisse) Multilingual Thesaurus on Land Tenure, Rome: FAO, 2003.

19 Cf. Jacques Gastaldi, “Les systèmes d’information foncière », in Lavigne Delville, Quelles politiques foncières pour l’Afrique rurale ? Paris : Karthala, Coopération française, 1998. pp. 449-460.

20 This is the system employed in France, except for Alsace and Moselle, where the German land registry system remains for historic reasons.

21 Cf. J. Comby, “La Gestation de la propriété”, in Lavigne Delville, Quelles politiques foncières pour l’Afrique rurale ? Paris : Karthala, Coopération française, 1998. pp. 701.

22 On 3 and 4 May 1493, only two months after Christopher Columbus’ return from his first voyage, Pope Alexander VI issued two bulls by which the crowns of Spain and Portugal were accorded ownership of the lands discovered or to be discovered, to the West of a determined line. These papal decrees determined once and for all the conditions of land ownership in Latin America: the land belongs to the government (first colonial, then republican), which in turn assigns it to individuals according to its own criteria. Cf. Olivier Delahaye, “Des bulles papales à la réforme agraire : la fabrication de la propriété foncière agricole en Amérique latine”, Revue Etudes Foncières # 89, January-February 2001.

23 Cf. debate on the indigenous lands of the Cordillera (Luzon) and the legal disputes related to the recognition of the rights of indigenous communities. Merlet Michel, Land tenure and production systems in the Cordillera, Mission report for the FAO, March 1996.

24 Cf. Joseph Comby,1998, ibid.

25 Cf. Jacques Gastaldi, “Land tenure information systems”, in Lavigne Delville, Quelles politiques foncières pour l’Afrique rurale ? Paris : Karthala, Coopération française, 1998, pp. 449-460.

26 Deininger, Klaus and Hans Binswanger, “The Evolution of the World Bank’s Land Policy: Principles, Experience, and Future Challenges”, The World Bank Research Observer, vol. 14, # 2. August 1999, pp. 247-276.

27 On this subject, refer to the text published on the World Bank site dedicated to land issues called, « Questions & Answers on Land Issues at the World Bank », a document prepared for the annual meetings of the Councils of Governors of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund Group. Washington, D.C.: 29-30 September 2001. The Bank recognises the failure of some of its previous programmes, such as that of assigning title deeds to land in Kenya. This text is an answer to the main questions asked at the World Bank on its actions related to land. Even though the practices of this institution do not always match its declarations on paper, it is interesting to observe the changes in its discourse, which would have been unimaginable ten years ago. A more recent World Bank Policy Research Report, “Land Policies for Growth and Poverty Reduction” written by Klaus Deininger confirms this. World Bank and Oxford University Press, 2003.

28 Etienne Le Roy explains in La sécurisation foncière en Afrique that the French civil code defines four statuses for land (public land, communal land, private domain, and private property). They are organised as a function of two oppositions between thing and good (non liable or liable to be converted into a commodity) and public and private (as a function of socially recognised use).

29 Etienne Le Roy, “La théorie des maîtrises foncières”, in E. Le Roy, A. Karsenty, A. Bernard, La sécurisation foncière en Afrique. Pour une gestion viable des ressources naturelles, Paris: Karthala, 1996. pp. 59-76.

30 Including Elinor Ostrom and E. Schlager « Property Rights Regimes and Natural Resources. A Conceptual Analysis, » Land Economics, August 1992.

31 Sources: J. Gastaldi, « Les plans fonciers ruraux en Côte d’Ivoire, au Bénin et en Guinée »; J.P. Chauveau, PM. Bosc, M. Pescay, « Le plan foncier rural en Côte d’Ivoire », in Quelles politiques foncières pour l’Afrique rurale ? Paris : Karthala, 1998 ; V. Basserie, KK Bini, G. Paillat, K. Yeo, « Le plan foncier rural: la Côte d’Ivoire innove … » Intercoopérants, Agridoc # 12.

32 A certain number of conditions lead to the privatisation of land, on the behalf of individuals and local authorities. Lands deemed ownerless are put under state ownership. Any land not registered after a certain period of time (3 years if there has been no temporary franchise, 10 years in the case of land over which customary rights are exercised peacefully) is deemed ownerless, and is thus taken over by the State. Owners are obliged to exploit their land, or else they risk losing their tenure rights.

33 This is a major political problem that goes beyond the framework of land security and illustrates a situation that often arises when land interventions get caught up in serious ethnic or political conflicts.

34 This appears to be the case at Mirriah, near Zinder, where the Land Commission was decentralised into a hundred Basic Land Commissions that work to recognise land rights shared by pastoralists, herdsmen-farmers and farmers. This authority has benefited from Danish and European cooperation for many years. In other regions however, establishing Land Commissions can provoke serious problems, and the effects depend on the current power play in the area and the possibility of changing it without too many conflicts, with or without external aid.

35 Sources: M. Mortimore quoted in P. Lavigne Delville, Rural land, renewable resources and development in Africa (bilingual French-English), Paris: Ministry of Foreign Affairs - French Cooperation, 1998.

36 Differences of this type are not limited to Africa alone. Similar contradictions exist in Central America between the land administration system set up by Spain and the one established in British protectorates. This is the case of Nicaragua, where the British protectorates on the Atlantic coast and the Kingdom of Mosquitia differ from the western part colonised by the Spanish. See M. Merlet, D.Pommier et al. IRAM. Estudios sobre la tenencia de la tierra au Nicaragua, a report done for the Oficina de Titulación Rural and the World Bank in 2000. See also the two experience records by Olivier Delahaye on the approaches to land in Venezuela and the USA in part II of this chapter.

37 See record # 3, part II of the paper.

38 The concept of “social capital” is often used today in discourses on poverty, to refer to standards, networks and institutions that enable community action. In other words, it describes the level of organisation of a society. The French term “capital social” has a different meaning, since it refers to a commercial or civil company’s property.

39 In the recent World Bank Policy Report Land Policies for Growth and Poverty Reduction, Klaus Deininger stresses that « building local capacities is essential ». He notes that « tenure security can be achieved under different forms of land ownership » and not only through « full ownership rights ». He also explains that a greater focus on local institutions is warranted, as well as paying attention to create awareness and to help people exercise their rights. This is a significant change in the World Bank analysis, as Deininger notes: « While the earlier report did not deal with institutions, it is now recognised that failure to do so can jeopardise implementation and should therefore be avoided. » (K. Deininger, ibid, pp. 186)

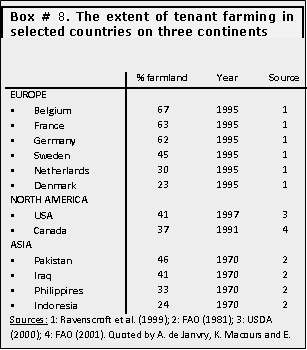

40 According to the FAO, the proportion of farmland under tenancy in 1970 (single and mixed: indirect and direct for the same farm) was 63% in North America, 41% in Europe, 32% in Africa, 16% in Asia and only 12% in Latin America. Source: A. de Janvry, K. Macours and E. Sadoulet, « El acceso a tierras a través del arrendamiento” in El acceso a la tierra en la agenda de desarrollo rural. Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo (Sustainable Development Department Technical papers series, RUR-108), 2002.

41 This procedure is essential for peasant economics, due to the variation through time of the availability of labour in a family farm (see the works of Chayanov)

42 See record # 14, part II of the Paper, C. Servolin, “DENMARK. Pioneer in peasant farming in Western Europe”

43 Main source: Rivera, Marie-Christine. « Le Foncier en Europe. Politiques des structures au Danemark, en France et au Portugal », (Land Issues in Europe. Policies and farm structures in Denmark, France and Portugal), Cahiers Options Méditerranéennes, vol. 36, 1996.

44 However, this kind of policy can now cause problems in regions where farm modernisation has led to the creation of large farms that rent land from a quantity of small landowners, who are actually bankrupted farmers.

45 See P. Lavigne Delville, C. Toulmin, J.P. Colin and J.P. Chauveau, Negotiating Access to Land in West Africa : A Synthesis of Findings from Research on Derived Rights to Land, London: IIED, GRET, IRD, 2002. 128p.

46 See Alain de Janvry, Karen Macours and Elisabeth Sadoulet, “El acceso a tierras a través del arrendamiento”, in El acceso a la tierra en la agenda de desarrollo rural, Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo. (Sustainable Development Department Technical papers series; RUR-108), 2002.

47 Sources: Beatriz B. Galán, Aspectos jurídicos en el acceso de la mujer rural a la tierra en Cuba, Honduras, Nicaragua y República Dominicana, FAO, 1998. and Sara Ceci, Women’s land rights: lessons learned from Nicaragua, December 2000.

Agter is part of the Coredem

Agter is part of the Coredem