- Accaparement des terres

-

Politiques foncières

- Refonder la politique foncière agricole de la France

- Politiques foncières et histoire agraire en Europe

- Les politiques foncières agricoles de la France au XXe siècle

- Le foncier en Afrique de l’Ouest. Fiches pédagogiques.

- Réformes Agraires dans le Monde

- Expérience du Code Rural au Niger

- Politiques foncières et Réforme Agraire. Cahier de Propositions.

- Forêts

- Eau

- Gouvernance des territoires

- FMAT - Forum Mondial sur l’Accès à la Terre 2016

- Autres Conférences et Forums internationaux

- Conférences filmées - Réunions Thématiques AGTER

- Entretiens avec des membres d’AGTER

- Formation - Enseignement

- Formation - Voyages d’étude

- Formation - Modules courts

- Editoriaux - Bulletin d’information d’AGTER

- Préserver l’environnement et les grands équilibres écologiques

- Développer la participation des peuples à la prise de décision aux niveaux national et local

- Respecter les droits humains fondamentaux. Lutter contre les inégalités

- Mettre en place une gouvernance mondiale efficace. Construire la paix

- Assurer l’efficience de la production agricole. En finir avec la faim

- Valoriser et entretenir la diversité culturelle

- Prendre en compte les besoins des générations futures. Gérer les « communs »

Recherche dans les titres, sous-titres, auteurs sur www.agter.org et sur www.agter.asso.fr

Recherche en plein texte sur www.agter.org avec Google

Rechercher dans le moteur Scrutari de la Coredem (multi-sites)

Version française de cette page : Gestion des sols et politiques foncières. Document introductif. EUROPE

Soil Management and Land Policies. Introductory document. Europe

WT54 workshop. China-Europe Forum

Rédigé par : Michel Merlet, Joseph Comby

Date de rédaction :

Type de document : Article / document de vulgarisation

Document written by Michel Merlet1 and Joseph Comby2

I. Workshop Description

« Land is, strictly speaking, the base of any workshop. In spite of modern technical developments, land is still the major condition of any sort of agriculture, thus of any subsistence. It is also the physical platform of every other human activity: dwellings, infrastructures and transportation, economic activity, public equipment, leisure activities. As such, it is the object of manifold competitions, and its assignment (as well as their rules of use) to the different activities and areas of society constitutes the foundation of social cohesion, the object of arbitrations and struggles, an essential sector of public and private law, and a major public policy domain.

Consequently, those policies, in China as well as in Europe, have two dimensions: one of them aims at ensuring soil quality and fertility for tomorrow’s agricultural production, and ways to distribute them to farmers in order to attain social equity, economic efficiency and long-term maintenance of this crucial production factor. As such, throughout history, agrarian policies have always been at the core of the organization of both European and Chinese societies. The second dimension, particularly pertinent to urban land policies and planning, aims at assigning certain economic and social activities to certain areas of land while regulating the conditions of competition between those different uses, and preserving the future.

In Europe, types of property and uses of agricultural land, along with modes of management of urban land, vary from one country to the next, thus offering a vast palette of different experiences. In China, the law passed at the beginning of the year 2007, by bringing the right to own land privately, represents a new major turn. In addition, the extremely fast economic and urban development of China, beyond comparison with that of the European Union, exacerbates the competition for the use of land and is the source of many social conflicts.

The goal of this workshop is to set European and Chinese experiences against one another, to identify which ones are the most cogent, and to define which partnerships ought to be the most promising in those domains for the upcoming decades. »

II. The workshop’s content - A threefold European proposal

Considering the time available for these workshops, we have opted for a European proposal giving priority to a limited number of themes that seem particularly important, both for Europe and for China. Many other choices would have been possible and interesting. We have chosen to address the following as priorities:

-

Modernization of agricultural structures and adaptations related to agriculture’s multifunctional nature.

-

Urban and industrial growth on agricultural lands, and the contradictions or conflicts thus generated3.

A third theme on soil management (in the pedological sense of the term), the problems of erosion, pollution, concreting, water management, and how they affect major society issues (food supply, global warming, energy challenges), is also proposed for discussion4.

III. Modernization of farming structures and adaptations related to agriculture’s multifunctional nature 5

A. Introduction

Predominately “peasant” type agricultural structures, that is, those in which the majority of farmland is worked by family production units using very few salaried employees, still represent, to this day, a considerable part of our planet’s rural space. Such “peasant” type structures vary greatly from one region to the next, depending on history, family structures, and cultures. They are in constant evolution, at ever increasing speeds. Commercial globalization affects their transformations considerably, and the survival of hundreds of millions of small growers is now endangered.

History has shown that family-based production forms have turned out to face the challenges of supplying food, creating wealth, maintaining natural resources, and creating jobs better than large salary-based production schemes.

Specific agricultural policies meant to accompany these evolutions and promote the modernization of farms without hoping to do away with family-based schemes should therefore come first on many countries’ agendas. In France, such policies for the modernization of family farming are called structures policies (politiques des structures), and we shall employ this term throughout the present proposal. Unfortunately, the very opposite is usually what happens. The farming issue is almost never addressed as such, neither by governments nor by international financial organizations. Even the countries that had placed such family farming policies at the core of their development strategies in the past now carefully avoid bringing it up, and often apply some radically divergent policies. Without a doubt, the main reason for this is that proposing any sort of market regulation is iconoclast in today’s world dominated by the single idea of free trade and laissez-faire.

Therefore, learning from past experiences, trading knowledge about what worked and what did not, or even just getting information about what was done in different parts of the world at different times, can prove to be difficult.

B. What is at stake in both China and Europe ?

Apart from both being characterized by small, family-based market production, Chinese and Western European farming structures are quite the opposite of one another.

Europe is certainly one part of the world that has accumulated some of the most experience about implementing structures policies, even if the term used in this document (politiques des structures) originates in France. They were of strategic importance in the establishment of the base of economic development. They stretched over several centuries, from the 18th century (Denmark) up to the late 20th (France, etc.), within economic and social contexts that have changed greatly. In some cases, they were truly public policies, established by governments. In other cases, those “policies” were a lot more implicit, based, for instance, on evolutions of the law or the tax policy, without any direct government intervention. Having never been designed as a common European policy, they remained national and little known, since documents dealing with them are usually available only in the language of the countries concerned.

The regulation of the rural exodus as a function of the forecasted labor absorption rate of industries and services, and the modernization of egalitarian agricultural structures resulting from China’s agrarian reform, are obviously among the major strategic questions of the upcoming decades. For this reason, these ought to be among the major themes of the China-Europe Forum.

-

Chinese agriculture is efficient; it incorporated the progress made by the green revolution without letting it cause massive impoverishment of the neediest classes. China, on the whole, is self-sufficient when it comes to food. The agrarian structures in place since de- nationalization are very egalitarian6, and land equality differs little between the North and South (an average 0.5 ha per family in the South, 0.8 in the North7). Family farming is meant first and foremost for auto-consumption, but also for sale, its income going toward farm inputs and taxes8. Engaging in multiple economic activities is the rule, but the growing difference in incomes between rural and urban areas make many villagers temporarily move to cities to work, without being able to permanently settle there due to the policy of household registration and binding rural populations to their birthplaces. Urbanization on former farmlands sometimes causes strong tensions. The development of intensive, often landless animal breeding units on the outskirts of large cities in order to supply food for the growing urban population, the shift to market prices for cereal, the consequences of joining the WTO, just to cite a few examples, raise some issues concerning the changes within the predominately “peasant” oriented rural world.

-

In rural areas, the recent passing of a private property law does not radically change farmers’ access to land, nor the level of security (or insecurity) of their tenure rights. However, it shows a general evolution. Understanding and discussing the nature of rights in rural lands, exploring the possible options to secure them, not in a “proprietaristic” way, but indeed in respect to multiple (individual, familial, collective, or even State) rights, definitely constitutes a project of great interest, for both today’s China and European countries9.

Structures policies also constitute a major cultural challenge for European countries, since many of them currently are implementing policies totally opposite of those that allowed their agricultural sectors and economies to develop in the first place. This challenge also exists for Eastern Europe countries recently integrated to the Union, and border countries such as Albania, Ukraine or Russia.

-

France is one of the countries that have pushed structures policies the furthest. But nowadays, one new farmer out of two settles without start-up grants. The structures policies are being questioned more and more.

-

The evolution of assistance policies (especially the single payment rights policies) radically changed the deal by making the right to receive assistance independent from the right to use the land. Also, the new Common Agricultural Policy created a radically new situation, which raises once more the issue of managing the evolution of farm structures and the rural world’s organization.

-

Integrating Spanish and Portuguese family farming into Europe caused some scarcely discussed but quick changes, deconstructing or eliminating these types of farming within entire regions. Integrating Eastern European farming raises some even more serious issues, since this entails the incorporation of highly polarized agrarian structures, thus far non-existent in Europe.

C. The European experiences

Only a few elements concerning European experiences in the field of structures policies shall be discussed here, as these are to be used as a reference for selecting the European participants.

1. Factors to take into account

-

Anthropological data – Family structures and inheritance types

The nature of family structures (relationships between parents and children) and the characteristics of inheritance systems (egalitarian or not) are particularly important since they largely determine the modes of maintenance or evolution of agrarian systems from one generation to the next.

Europe is highly diversified in this domain, as the following maps, taken from Emmanuel Todd’s work, demonstrate10. The limits do not at all correspond to the current international borders.

-

Historical data: the British Isles and the Continent. The countries of Eastern Europe (2nd serfdom)

History has determined very different characteristics, especially concerning the nature of rights in land and the rules that govern their application. Feudal systems have evolved continuously on the British Isles, while they were broken by the French revolution in France and on the Continent. Systems related to the Common Law system, on one side of the English Channel and from the Napoleonic Code (Le Code Civil), on the other side, led to very different situations concerning the management of rights in land, featuring either multiple property rights or one absolute property right (ownership).

The distribution of agrarian systems, of growing systems, the greater or lesser importance of large estates, also result from these complex historical evolutions. The illustrations included in this document, also taken from Emmanuel Todd’s work, provide a very simplified view of it.

Another major difference comes from the greater or lesser importance of indirect land use (sharecropping, tenant farming) as a mode of farmland use.

The laws on tenant farming in France made a priority out of securing the use rights of farmers. In some other countries, acquiring land through property was favored above all else.

The development of large farm estates owned by landlords and the disappearance of peasant farmers after the enclosures movement on a large part of the British Isles is quite different from the agrarian systems on the Continent. However, other parts of those islands underwent specific evolutions, such as the crofts in Scotland, which heavily secured the farmers’ rights under a still-feudal agrarian regime.

Far Southern Europe demonstrates different characteristics, and highly unequal land access, which necessitated agrarian reforms (Portugal, Spain, Italy).

In Eastern European countries, agrarian histories have been just as diverse and display different characteristics than those of the West as well11.

Fiscal regimes have varied greatly. Sometimes there were income taxes based on land holdings, on land transactions, or on inheritances.

Moreover, land policies ought not to be understood outside of their original historical context. The political situation (rights to vote, the way legislative decisions are made) should be taken into account, as well as the major tendencies in the evolution of prices of agricultural products (very different depending on the various periods), the tendencies in the evolution of land prices, the evolution of the importance of agriculture, agricultural decline (rural exodus, faraway migrations), returning to the land, conflicts on account of urbanization, and of course technical evolutions and compatibility between plots and new production systems. Last but not least, one should consider the producers’ level of organization and how rural society functions, for these things can vary considerably from one region to the next.

Neglecting to consider a structures policy in its original historical and geographical context would prevent any possibility for interpreting its success or failure, and would block the possibility of using it while developing strategies in other contexts. The laws on tenant farming implemented in Spain, which were inspired by French laws, failed to produce the same results. In some cases caused consequences nearly opposite to those expected since the amount of land available for renting actually decreased.

Because of these difficulties, a sufficiently precise study is necessary in order to be able to learn from what has been but a huge laboratory, whose interest goes far beyond that of the sole European Continent.

Since we are already in contact with a certain number of resource persons, who reflect the diversity of European experiences, we count on being ready to assemble a panel of guests that is able to deal with this complex issue.

2. A glimpse at a few national policies undertaken in certain European countries

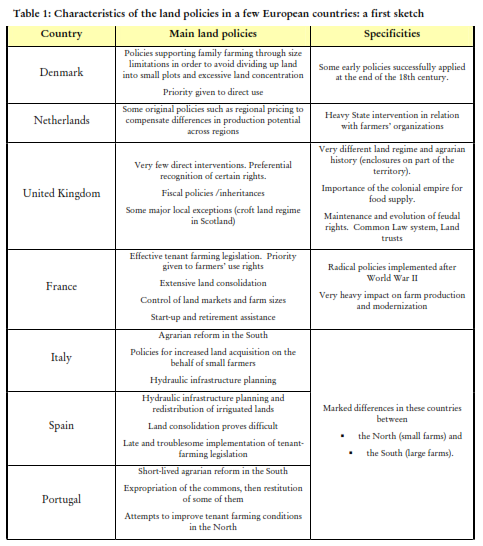

We are using here the work done by Maribel Hernandez in 200112, which constituted a preliminary exploration of this issue for France, Italy, Spain, Portugal and Denmark. We have added to this first comparative table with partial data from Netherlands and United Kingdom.

3. Recent changes

The development of family farming has been radically modified by the enactment of the Common Agricultural Policy, as well as by the changes in the European Union’s trade policy and the expansion of the Union. These changes should call for major developments that wouldn’t quite belong within the limited range of this presentation. Changing agricultural structures in the older member States, as well as the specific issues raised by the evolution of agricultural structures in Eastern Europe countries, should be addressed by the participants.

IV. Land Issues Related to Urban Expansion in Europe 13

A. Why cities need to expand

Due to the long-term increase in living standards, the dwelling surface area per European habitant has grown (in France, between 1972 and 2002, the per inhabitant surface of the main residence increased by 48%).

The ratio of building for other purposes than creating living spaces (offices, economic activities, warehouses, miscellaneous equipment) is under slow but continuous progression too, enough so that its physical volume now represents slightly more than half of the entire building activity.

The historical migration process from rural areas toward cities is now finished, and the demographic rise is almost zero now that the lifetime increase just compensates the birth rate decline. However, an increase in foreign immigration is recorded, especially in large metropolises, which also contributes (though to a lesser extent) to large cities’ need to expand.

In a general way, urban constructed areas double about every 40 years (this estimate is given with every reservation, for lack of any statistics on this subject).

B. Two alternatives: extension (sprawl) and densification

Increasing a city’s constructed area can be achieved by either making the existing urban areas denser (densification) or by expanding the said areas (expansion/sprawl). Public policies generally try to favor densification for a number of reasons:

-

a) preserving natural and agricultural space,

-

b) reclaiming abandoned industrial unused lands,

-

c) reducing commutes to protect the environment

However, city growth by means of urban sprawl outweighs the densification option for multiple reasons:

-

a) the desire to preserve the historical centers of old European cities

-

b) commutes have been technically and economically assisted (nearly every household now owns a private car except for elderly people and a small number of people who live in the centers of major metropolises) and the price of energy is still relatively low.

-

c) appeal of the individual house as a form of living space

-

d) large surfaces are needed for production (the former urban workshops have disappeared), storage, and distribution (development of large shopping centers)

-

e) desire for “nature” as much for living spaces as for centers of economic activity.

In the end, records usually display a real densification of the built-up areas of old urbanized spaces (in terms of square meters of floor space per hectare), accompanied by a sizeable de-densification in terms of number of inhabitants and/or jobs per hectare.

C. Land matters and urban sprawl

Letting land markets run their course would induce a “spilt oil” type urban sprawl, which is usually not wanted. Therefore, mastering and organizing that sprawl, while keeping it compact to some extent (either by extending existing urbanized spaces or, on the contrary, by creating secondary growth poles) constitutes a primary goal.

The second goal is a financial one. It consists in determining who shall fund urban planning (preparation, draining, extension of networks etc.). Four options exist, which may be used simultaneously in different proportions depending on the case:

-

a) funding by public budgets, i.e. by taxpayers as a whole (the city’s taxpayers only in the case of municipal funding, national taxpayers as a whole if government grants exist).

-

b) funding by builders, who shall forward that cost on to final buyers (through the price of rent or purchase)

-

c) funding by blocking original landowners from capitalizing upon the increased real estate value of newly urbanized lands

-

d) funding by future users by charging fees for the use of every service and equipment (for instance, the water and sewage network, whose construction is funded by a loan that will be paid by advance payments of future water bills by the neighborhood’s inhabitants, rather than including the installation cost in the sale price of the new dwellings).

D. Governing urban sprawl

The geographical scope of land governance under suburbanization can lead to different choices depending on whether it is up to the authorities of the city generating the said expansion, or to the smaller municipality onto the territory of which the expansion occurs. The size of municipalities able to undertake land planning differs greatly among European countries.

Juridical tools that may be used by local authorities to direct such planning fall into several categories:

-

a) regulations that determine authorized and restricted forms of land use depending on the zone

-

b) juridical tools that intervene in land appropriation (expropriation, pre-emption)

-

c) possibility to negotiate with landowners about lifting certain restrictions under certain conditions

-

d) operational tools enabling local bodies to negotiate programs with planners and constructors

-

e) the technical and financial capacity to partake directly or indirectly in urban planning and development.

Actions concerning land (purchases, merging plots, resale) prior to planning, can be conducted either directly by local authorities, or entrusted to an outsider with the technical and financial means to act in their place, or merely left to private agents.

V. ANNEXES

A. Planning the workshop

We suggest organizing the workshop in several steps.

-

June 2007

ƒ-- Preparation of the first part of the introductory document, presenting the major regional specificities and the main issues to be discussed from the European point of view.

ƒ-- Selection of the participants, suggestion for the workshop’s keystone and approval by the Forum committee.

-

July and August 2007

ƒ-- Organizing with the European participants. A short written contribution is asked from each of them. One or two preparatory meetings are to be held and to be entered into the accounts so as to avoid any excessive waste of time during the workshop itself.

-

- Selection of the Chinese participants by the Forum’s organizing committee, and preparation of the Chinese part of the introductory document.

ƒ-- Talk with members of AGTER familiar with Chinese issues, in order to finalize the definitive version of the workshop’s introductory document, in English and in Chinese. English (and Chinese?) translations of the participants’ documents are also to be planned for August and September.

-

October 2007

ƒ-- Holding the workshop

ƒ-- Preparation of summary documents

The logistical part of the workshop’s preparation is taken care of as of now.

B. Follow-up work that AGTER wishes to organize concerning the “agricultural structures” part

We develop this section for informational purposes only; it does not imply any engagement from the FPH to contribute to the funding of its activities. AGTER seeks to build the partnerships necessary to carry them out.

Such a workshop is rather pointless if no further work between Chinese and European partners can come out of it. To make such cooperation possible, we wish, starting now, to plan:

-

The establishment of a one- to two-year reflection project on Europe’s structures policies. This involves the preparation of a collective report containing records written in collaboration with resource persons. This report will be composed of:

-

A series of well-documented records that convey the most important experiences in European structures policies.

-

A section of comparative analysis calling upon the contributions of different participants, which may lead to the development of proposals that may interest governments and farmers’ organizations in countries needing policies for the modernization of their agricultural sectors

-

ƒ- Preparation of a study trip for Chinese participants interested in European issues, to see and better understand the nature of the challenges of structures policies, and a parallel trip to China for a small group of work partners, in order to better perceive the goals and specificities of this country.

ƒ- Once we have included the contributions of those who participated in the fieldwork trips, we

will be able to finalize the reflection project’s final report, which will be made available in various forms, including as an electronic resource in AGTER’s web database.

Considering that this issue is dealt with in so many countries worldwide, it would be highly interesting to collaborate with associates coming from different parts of the world. We have in mind, in particular, some ex-socialist countries (Albania, Georgia, Vietnam…) and some countries of Latin America (Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, Chile, Peru…), as well as some countries from North, West and East Africa, and some states of India.

Thus, our proposal falls within a participative research project. A crucial element of what we propose is to align our work with what countries are asking for, as much through their official decision-making bodies as through their farmers’ organizations.

The development of a future partnership with China is clearly central to this plan; yet, it will be enriched if the process is broadened to incorporate other nations and continents.

1 Director of the Association for Improved Land, Water and Natural Resource Governance (AGTER), www.agter.asso.fr/

2 Chief Editor of the Revue Etudes Foncières and founding member of ADEF, the Association for Development of Land Studies.

3 Specific issues concerning urban land will not be discussed as such. The WT42 workshop about urban management should allow us to take them into account.

4 A distinct introductory document is being prepared by Rabah Lahmar.

5 Michel Merlet, with Sylvie Dideron, member of AGTER, June 2007.

6 Unlike distribution of income in China. See the work of Claude Aubert about China.

7 The only exception is Manchuria, with an average of 1.5 ha of cultivated lands.

8 To lighten the load of local agricultural taxes, those have been dramatically reduced since early 2000, or even eliminated in the poorest areas

9 See the work of Terre de Liens (terredeliens.org/)

10 Emmanuel Todd. L’invention de l’Europe. Ed. Seuil. Paris. Mai 1990.

11 The Russian feudal system, featuring second serfdom, maintenance of the rural community (obscina), and very particular family structures, make any grafting of the Western European policies a tricky enterprise, as Vladimir Yefimov admirably shows. [Vladimir Yefimov, 2003, Economie institutionnelle des transformations agraires en Russie, Paris:L’Harmattan]. To learn more about those Eastern Europe countries, the following is also recommended: Lerman, Csaki, Feder, 2001, Land Policy and Changing Farm Structures in Central Eastern Europe and Former Soviet Union.

12 M. Hernandez, Ejemplos de polìticas de tierra en varios paìses de Europa occidental. August 2001. Maribel Hernandez is a member of AGTER.

13 Joseph Comby – 11 july 2007

Télécharger le document

-

fcn_2007_proposal_workshop_agter_en.pdf (500 Kio)

Agter participe à la Coredem

Agter participe à la Coredem